To what extent do you own your own face? Or fingerprints? Or DNA? How far would you trust others to use such sensitive biometric data? To ask these questions is to highlight the uncertainty and complexity surrounding their use. The short, if messy, answer is: it all depends on context.

Many people, including me, would happily allow trusted medical researchers combating genetic diseases to study their DNA. Few object to the police selectively using biometric data to catch criminals. Remarkably, in 2012 German detectives solved 96 burglaries by identifying the earprints of a man who had pressed his ear to doors to check no one was at home. On-device identity verification using fingerprint or facial recognition technology for a smartphone can enhance security and convenience.

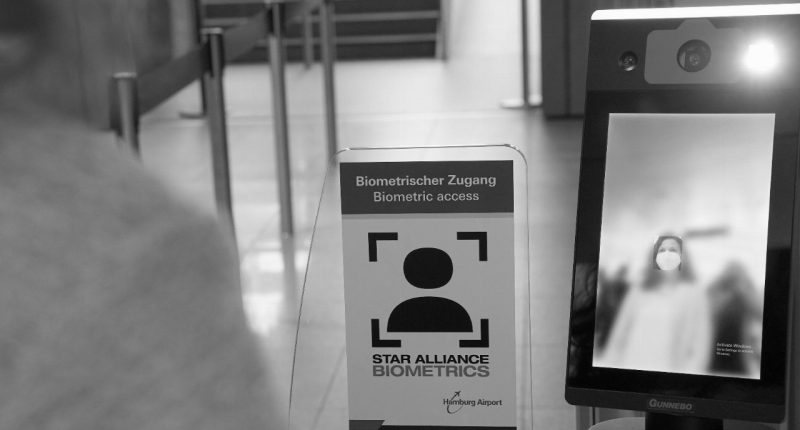

But the scope and frequency of biometrics usage is exploding while the line between what is acceptable and unacceptable is growing fuzzier. Already one can point to reckless or malign uses of biometrics. The companies that use the technology and the regulators that oversee them have an urgent responsibility to draw a clearer dividing line. Otherwise, worries will grow that we are sleepwalking towards a surveillance state.

The most glaring concern about the use of such data is how it strengthens surveillance capabilities in ways with no accountability, most notably in China which rigorously monitors its own population and exports “digital authoritarianism”. A 2019 report from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace found AI-enabled surveillance technology was being used in at least 75 of the 176 countries it studied. China was the biggest supplier of such technology, selling to 63 countries, while US companies sold to 32 countries.

But the use of biometric data is also being enthusiastically adopted by the private sector in workplaces, shops and schools around the world. It is used to verify the identity of taxi drivers, hire employees, monitor factory workers, flag shoplifters and speed up queues for school meals.

A powerful case for why politicians need to act now to create a stronger legal framework for biometric technologies has been made by the barrister Matthew Ryder in an independent report published this week. (For disclosure: the report was commissioned by the Ada Lovelace Institute and I am on the charity’s board.) Until that comes into force, Ryder has called for a moratorium on the use of live facial recognition technology. Similar calls have been made by British parliamentarians and US legislators without prompting much response from national governments.

Three arguments are made as to why politicians have not yet acted: it is too early; it is too late; and the public does not care. All three ring hollow.

First, there is a case that premature and proscriptive legislation will kill off innovation. But big US companies are themselves growing increasingly concerned about the indiscriminate proliferation of biometric technology and appear fearful of being sued if things go horribly wrong. Several — including Microsoft, Facebook and IBM — have stopped deploying, or selling, some facial recognition services and are calling for stricter legislation. “Firm regulation helps innovation,” says Ryder. “You can innovate with confidence.”

The next argument is that biometrics are developing so fast that regulators can never catch up with frontier uses. It is inevitable that technologists will outrun regulators. But as Stephanie Hare, the author of Technology is Not Neutral, argues, societies are allowed to change their minds about whether technologies are beneficial. Take asbestos, which was widely used for fire prevention before its dangers to health became known. “We used it with joy before we ripped it all out. We should be able to innovate and course correct,” she says.

The final argument is that the public does not care about biometric data and politicians have higher priorities. This may be true until it no longer is. When citizens’ councils have studied and debated the use of biometric data they have expressed concern about its reliability, proportionality and bias and alarm about it being used as a discriminatory “racist” technology. Research has shown that facial recognition works least accurately on black female 18- to 30-year-olds. “When you see technology being used in a nefarious way, it then makes it difficult for people to accept it in more useful ways,” one participant in a citizens’ council said.

Everyone involved in promoting the positive uses of biometric data should help create a trustworthy legal regime. We are one giant scandal away from a fearsome public backlash.

John Thornhill is the Innovation Editor at the Financial Times writing a weekly column on the impact of technology. He is also the founder and editorial director of Sifted, the FT-backed site for European startups, and founder of FT Forums, which hosts monthly meetings for senior executives.

John was previously deputy editor and news editor of the FT in London. He has also been Europe editor, Paris bureau chief, Asia editor, Moscow correspondent and Lex columnist.