One of the more insidious forms of internet clickbait asks what has become of this or that celebrity, usually one who shone brightly but briefly and now hawks steak knives on the Shopping Channel or practices an artisanal craft somewhere in rural Italy. Equal amounts of curiosity and schadenfreude fuel our interest in such (non) stories, which generally tell us few truths except that famous people are as imperfect and mercurial as the rest of us.

Then there are celebrities like Russell Brand. If, like me, you’d half-forgotten about the Essex-born comedian and actor, a quick update: Having risen to fame via his portrayal of rock star Aldous Snow in the 2008 romantic comedy-drama Forgetting Sarah Marshall, Brand built a successful career around playing versions of himself — impish, verbose, and seemingly always elegantly wasted — while rolling out variously popular and contentious books, stand-up tours, and presenting gigs. His penchant for rock star-like outrageousness, combined with his brief marriage to American singer Katy Perry, made him a tabloid editor’s dream, even if the hijinks belied an intellect many of his posher interlocutors chose to ignore (some, like Newsnight host Jeremy Paxman, at their peril).

In 2013 Brand took a hiatus from acting, no doubt stung by the mostly negative reception of films like Arthur — an unnecessary remake of the 1981 Dudley Moore vehicle — and the animated Hop. Two years later, perhaps with one eye on his past as a radio presenter, Brand launched his first podcast, followed by another, Under the Skin with Russell Brand, in 2017. Described as “a voyage of learning”, the podcast runs, as of the time of writing, to 281 episodes, the latest of which features cult British documentarian Adam Curtis. Many interviews sit somewhere on the new age/self-help/wellness spectrum — there are episodes on “finding your focus”, “vulnerability and power”, “how to be a loving man”, and so on. Guests in this vein have included Eckhart Tolle of Power of Now fame and Deepak Chopra, the inexplicably bestselling author of nearly a hundred pseudoscientific books on consciousness, ageing, and spirituality.

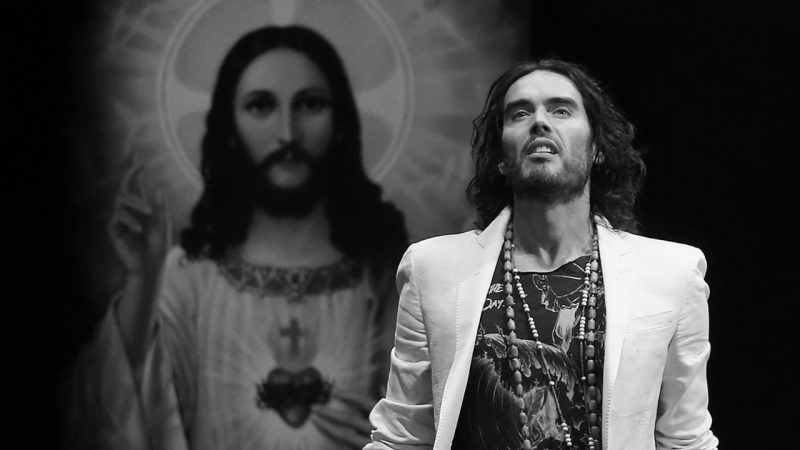

Brand has long since swapped his rock god look for what we might call guru chic — white, loose-fitting shirts and cardigans, beaded necklaces, Jesus locks. His podcasting, lest this description give the impression of a man having achieved a fallow level of spiritual enlightenment, is prolific. As well as Under the Skin, he also hosts Stay Free with Russell Brand, which streams to Rumble five times a week and currently has 6.19 million subscribers on YouTube. As with Under the Skin, his guests on Stay Free are a grab-bag of writers, actors, academics, and acknowledged or professed public intellectuals.

It wouldn’t be a stretch to describe Stay Free as an English Joe Rogan Experience. Both Brand and Rogan disdain the mainstream media, assert their transcendence of conventional, two-party politics, and present themselves to their enormous audiences as truth-tellers unafraid to challenge the narratives meekly accepted by most of us. Both have also promulgated COVID misinformation and various conspiracy theories, and platformed ultra-conservative bloviators like Jordan Peterson and Ben Shapiro in the name of open discourse (Rumble, Brand’s hosting service of choice, is well known for attracting the US right and far-right). While all of this might seem like an unlikely path for an actor-comedian who made his name in the R-rated comedy boom of the naughties, the signposts have arguably been visible from the beginning.

Like the late, great critic and theorist Mark Fisher, I was once sympathetic to Brand. To propel the discussion of the still taboo topic of class into anodyne debates about inequality and the redistribution of wealth was no mean feat; that Brand was able to do so with more irreverence than piousness, and in a voice that went against the grain of the throughly bourgeois contemporary left, bordered on miraculous. As Fisher explained in a much-discussed 2013 piece, “Exiting the Vampire Castle”:

“The day before Brand’s now famous interview with Jeremy Paxman was broadcast on Newsnight, I had seen Brand’s stand-up show the Messiah Complex in Ipswich. The show was defiantly pro-immigrant, pro-communist, anti-homophobic, saturated with working-class intelligence and not afraid to show it, and queer in the way that popular culture used to be (i.e. nothing to do with the sour-faced identitarian piety foisted on us by moralisers on the post-structuralist “left”). . . . This was communism as something cool, sexy and proletarian, instead of a finger-wagging sermon.”

Fisher, tragically, did not live long enough to have to revise his opinion of Brand, an exercise I think he would have found impossible to dodge. I have little doubt he would have found Brand’s embracement of COVID contrarians and “New World Order” conspiracy theorists like Jeffrey Sachs and John Campbell alarming, if not disqualifying. I suspect he would have also found Brand’s take on the war in Ukraine — that it has infinitely more to do with the United States’ aggressive imperialist agenda than Putin’s — as half-baked as I do.

But Fisher missed the clue: the title of Messiah Complex, like Brand’s portrayal of God in the widely panned Army of One opposite Nicholas Cage, was only ever half a joke. The humility necessary to get away with such apparently unserious self-aggrandisement now eludes Brand entirely. He has, in a phrase, begun to believe his own bullshit.

Once, what Fisher called “Brand’s extraordinary breach of the bland conventions of mainstream media ‘debate’” felt like a breath of fresh air. Now, wafted out daily to his millions of disciples, it carries the unmistakable stench of an undergraduate perpetually discovering Noam Chomsky for the first time. Contrarianism has its place as an occasionally useful tool for seeing through established values, practices and stories, which generally aid the interests of the powerful and oppressive. But if holding your door open to all comers means being receptive to every harebrained idea that comes through it too, then what, really, is the point? (As the old adage goes, keep an open mind, but not so open your brain falls out.) The fact that Brand has said he wants to interview both Trump and AOC is supposed to impress us in its lack of partisanship, but rather it smacks of someone who, like Trump, is chiefly interested in manoeuvring himself closer to rich and influential people so as to inflate his own profile. That isn’t iconoclasm; it’s just a grift.

The self-appointed guru always puts it this way: “There is an elemental truth that you cannot see because you don’t want to or because it has been concealed from you, but I have special access to it. Listen to me (and hit that subscribe button!), and you too will be awakened.” The fact that Brand now makes a living spouting this sort of exalted garbage, while denigrating the “dumb numbness” of those who consume mainstream news, makes me wonder if Brand’s class consciousness was never more than a part of, well, the brand. Where once the likes of Jeremy Paxman spoke down to Brand as a “class inferior”, the guru now speaks down to all of us.

Brand is right to challenge the venality of mass media, the state, and big business. But to do so without a politics, in a world where you’re happy to kick back with the likes of Elon Musk and in which “republicans, libertarians, Trump voters, and social justice warrior democrats” are all equally desirable apostles, amounts less to what Brand once called “revolution” than sheer narcissism. Get him to the greek!

Ben Brooker is a writer and critic based in Naarm (Melbourne), Australia. He is working on his first book, a cultural history of psychedelics in Australia.

Stay up to date on all the latest commentary, analysis and opinion pieces from Art of the Essay by following on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn.