Until the early 1980s, Australian politics was dominated by the fight between the conservative right of the country, represented by the Liberal-National Party Coalition (and its earlier iterations), and the working-class left of the country, represented by the Labor Party.

To call this a two-party system was always a bit of a fudge, given the Coalition itself consisted of two parties, the metropolitan-based Liberal Party and the rural-based National Party (and, later, the amalgamated LNP in Queensland). But the truth is, most people thought of the LNP as a single entity, and in many key respects it was. Certainly, the media presented it as such.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the arguments between the “two” major parties cleaved strongly to international divisions between left and right, between socialism and free-market economics, but by the time of the Hawke-Keating government, these categorisations were collapsing. Once the Labor Party went all-in on neoliberal economics — whatever social safety net they put in place with it — the old class divisions started to transform and lose their electoral power of definition, and our sense of personal and national identity shifted with it.

Inevitably, so did our voting habits.

Those changes came to a head in the federal election of 2022, and the biggest political story to emerge this year was not just that Labor was returned to power for first time in nearly decade, but that the entire logic of our two-party system was undermined.

The latest Australian Election Study (AES), put together by the School of Politics & International Relations at the Australian National University, collects data on how and why people vote the way they do, and what emerges is a realignment of the two-party system we have taken for granted, with both “major” parties diminished. The outlook, though, is particularly bleak for the once-mighty Liberal Party of Australia, and it is the nature of their decline that suggests the 2022 result is not an aberration but the consolidation of a long-term trend.

A key figure provided by the AES is that people “are more likely to switch their votes from election to election than ever before, with only 37 per cent of voters supporting the same party at each election.” This is an extraordinary figure and undermines completely the notion that Labor and the Coalition can rely on a cohort of “rusted on” voters to deliver them turns in government. And while this trend introduces some volatility into election outcomes, the main point to make is that it means voters are more open to alternatives than they have ever been, and therefore that many “truisms” of Australian politics no longer hold.

Further evidence that we’re talking permanent electoral change rather than a 2022 aberration emerges when we look at voting patterns based on age. What is important to note is that unlike in the past, where voters became more conservative as they aged, the 2022 election result suggests this trend has been well-and-truly broken, which is further bad news for the Liberals.

The AES notes that, between the elections of 2016 and 2022, “Millennials record a large decline in Coalition support, falling from 38 per cent to 25 per cent in just two election cycles.” As well, the Coalition only picked up 26 per cent of votes from Generation Z — who were born after 1996, and so only voted in 2019 and 2022 — while 67 per cent of that cohort voted either for the Greens or Labor. The AES notes that “no other generation records such skewed preferences at similarly early stages of the life course.”

Generation X, who are first recorded by the AES in 1987, show “40 per cent reporting support for the Coalition, with a slight trend away from this level in the 35 years since.” And while Labor has lost direct support amongst this generation too, it has come back to them in two-party preferred terms “by Generation X’s turn towards the Greens.”

Again, all this suggests ongoing structural change, and bigger problems for the Coalition than for Labor, and for the Liberals than for the Nationals — patterns that are also reflected in the changing nature of class in Australia. The AES notes that, “class remains an important influence on voting, despite having declined from its peak in the 1950s,” and that the “modern expression of class is how people identify themselves, in the economic assets that they own, and the social capital they possess.”

The data shows that “working class voters remain more likely to vote Labor than Liberal,” but that “their support for Labor has diminished over time.” So, while “48 per cent of the working class voted Labor in 2016, this dropped to 38 per cent in 2022,” and the “Liberal vote declined to a similar degree.”

To the extent that home ownership is an indicator of class and that it influences voting decisions, again, the news is not good for the Liberal Party. As the number of people renting rather than owning increases, the demographic makeup of even “safe” Liberal seats changes, making them far less safe, as we saw in 2022.

The AES notes, “homeowners were more likely to vote for the Coalition in 2022, while renters were more likely to vote Labor,” but “the voting gap between homeowners and renters has reduced significantly since 2019. The proportion of homeowners voting for the Coalition declined from 50 to 38 per cent, in favour of minor parties and independents, while the voting behaviour of renters was similar across the two elections.”

To get a full sense of what all this means, and how the changes call into question the ongoing viability of the Liberal Party, consider these results from the 2022 federal election.

Of the 15 electorates with the highest median income in the country, the Liberal Party now holds none of them. Zero. They used to hold 14 of the 20 wealthiest electorates in the country, and they now hold five. They lost support amongst the university educated and, incredibly, amongst those attending private schools. The party would need to win 18 seats to regain government at the next election, and analysis by David Tanner at The Australian suggested that if, as Peter Dutton and others have said, they were to concentrate on outer metropolitan seats rather than the “teal” seats they lost in 2022, they are likely fighting a losing numbers game.

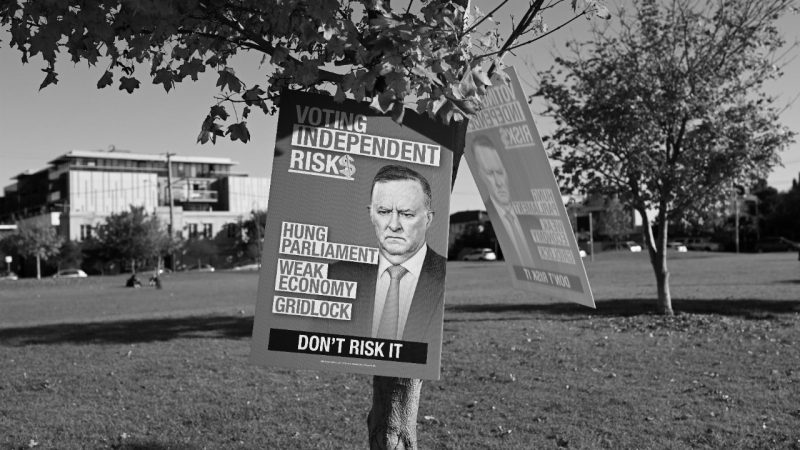

Whether we are moving to a permanent state of minority government remains to be seen, but perhaps the biggest clue that the parties themselves think it might be the new normal is the fact that Liberal leader Peter Dutton conceded in a recent interview that he would be willing to do a deal with “teals”, with the crossbench, if that is what it took to form government. You could not get a clearer statement of the fact that politicians themselves think the two-party system may well be in its death throes.

Clearly, the Liberal Party needs to rethink its election strategies, their representation, and, in fact, their entire raison d’être. But to frame the issue in that way — as if the health of Australian democracy presumes a strong Liberal party — is deeply misleading.

There is much talk amongst the political class that democracy requires a strong opposition to function properly, and there is some truth in that. But there is nothing in the logic of that claim that means the opposition must consist of a single, major party, let alone that it must be the Liberal Party of Australia.

If voters are convinced independents, or candidates from smaller parties, will represent their views and their values, the evidence shows they are more than willing to give them their vote. This may be bad news for the major parties — and on current trends for the Liberals in particular — but voters are showing that they think it is good news for democracy.

Tim Dunlop is Melbourne-based writer. His new book, Voices of Us, about the rise of the “teal” independents, was released on 1 December.