In the 1950s, Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita” was banned in France, Britain and Argentina, but not in the United States, where its publisher, Walter Minton, released the book after multiple American publishing houses rejected it.

Minton is part of a noble tradition. Over the years, American publishers have fought back against efforts to repress a wide range of works — from Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” to Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” Just last year, Simon & Schuster defended its book deal with former Vice President Mike Pence, despite a petition signed by more than 200 Simon & Schuster employees and other book professionals demanding that the publishing house cancel the deal. The publisher, Dana Canedy, and chief executive, Jonathan Karp, held firm.

The U.S. publishing industry has long prided itself on publishing ideas and narratives that are worthy of our engagement, even if some people might consider them unsavoury or dangerous, and for standing its ground on freedom of expression.

But that ground is getting shaky. Though the publishing industry would never condone book banning, a subtler form of repression is taking place in the literary world, restricting intellectual and artistic expression from behind closed doors and often defending these restrictions with thoughtful-sounding rationales. As many top editors and publishing executives admit off the record, a real strain of self-censorship has emerged that many otherwise liberal-minded editors, agents and authors feel compelled to take part in.

Over the course of his long career, John Sargent, who was chief executive of Macmillan until last year and is widely respected in the industry for his staunch defence of freedom of expression, witnessed the growing forces of censorship — outside the industry, with overt book-banning efforts on the political right, but also within the industry, through self-censorship and fear of public outcry from those on the far left.

“It’s happening on both sides,” Sargent told me recently. “It’s just a different mechanism. On the right, it’s going through institutions and school boards, and on the left, it’s using social media as a tool of activism. It’s aggressively protesting to increase the pain threshold, until there’s censorship going the other way.”

In the face of those pressures, publishers have adopted a defensive crouch, taking preemptive measures to avoid controversy and criticism. Now, many books the left might object to never make it to bookshelves because a softer form of banishment happens earlier in the publishing process: scuttling a project for ideological reasons before a deal is signed or defusing or eliminating “sensitive” material in the course of editing.

Publishers have increasingly instituted a practice of “sensitivity reads,” something that first gained traction in the young adult fiction world but has since spread to books for readers of all ages. Though it has long been a practice to lawyer many books, sensitivity readers take matters to another level, weeding out anything that might potentially offend.

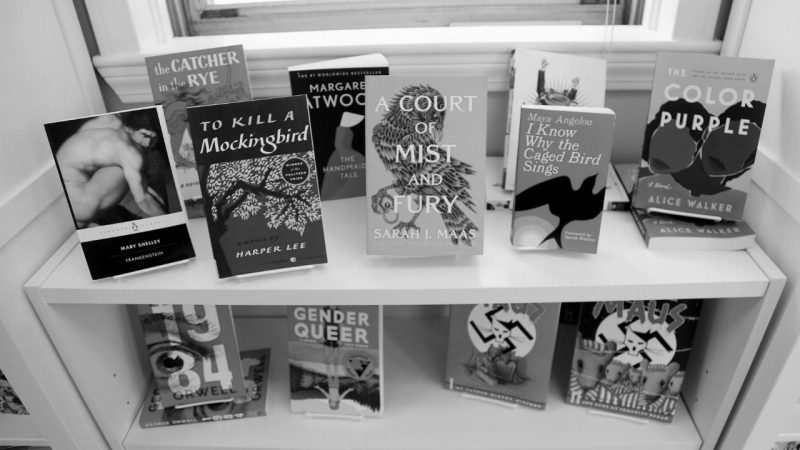

Even when a potentially controversial book does find its way into print, other gatekeepers in the book world — the literary press, librarians, independent bookstores — may not review, acquire or sell it, limiting the book’s ability to succeed in the marketplace. Last year, when the American Booksellers Association included Abigail Shrier’s book, “Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters,” in a mailing to member booksellers, a number of booksellers publicly castigated the group for promoting a book they considered transphobic. The association issued a lengthy apology and subsequently promised to revise its practices. The group’s board then backed away from its traditional support of free expression, emphasising the importance of avoiding “harmful speech.”

A recent overview in Publishers Weekly about the state of free expression in the industry noted, “Many longtime book people have said what makes the present unprecedented is a new impetus to censor — and self-censor — coming from the left.” When the reporter asked a half dozen influential figures at the largest publishing houses to comment, only one would talk — and only on condition of anonymity. “This is the censorship that, as the phrase goes, dare not speak its name,” the reporter wrote.

The caution is borne of recent experience. No publisher wants another “American Dirt” imbroglio, in which a highly anticipated novel was accused of capitalising on the migrant experience, no matter how well the book sells. No publisher wants the kind of staff walkout that took place in 2020 at Hachette Book Group when journalist Ronan Farrow protested its plan to publish a memoir by his father, Woody Allen.

It is certainly true that not every book deserves to be published. But those decisions should be based on the quality of a book as judged by editors and publishers, not in response to a threatened, perceived or real political litmus test. The heart of publishing lies in taking risks, not avoiding them.

You can understand why the publishing world gets nervous. Consider what has happened to books that have gotten on the wrong side of illiberal scolds. On Goodreads, for example, vicious campaigns have circulated against authors for inadvertent offences in novels that haven’t even been published yet. Sometimes the outcry doesn’t take place until after a book is in stores. Last year, a bunny in a children’s picture book got soot on his face by sticking his head into an oven to clean it — and the book was deemed racially insensitive by a single blogger. It was reprinted with the illustration redrawn. All this after the book received rave reviews and a New York Times/New York Public Library Best Illustrated Children’s Book Award.

In another instance, a white academic was denounced for cultural appropriation because trap feminism, the subject of her book “Bad and Boujee,” lay outside her own racial experience. The publisher subsequently withdrew the book. PEN America rightfully denounced the publisher’s decision, noting that it “detracts from public discourse and feeds into a climate where authors, editors and publishers are disincentivised to take risks.”

Books have always contained delicate and challenging material that rubs up against some readers’ sensitivities or deeply held beliefs. But which material upsets which people changes over time; many stories about interracial cooperation that were once hailed for their progressive values (“To Kill a Mockingbird,” “The Help”) are now criticised as “white saviour” narratives. Yet these books can still be read, appreciated and debated — not only despite but also because of the offending material. Even if only to better understand where we started and how far we’ve come.

Having both worked in book publishing and covered it as an outsider, I’ve found that people in the industry are overwhelmingly smart, open-minded and well-intentioned. They aren’t involved in some kind of evil plot. Book people want to get good books out there and to as many readers as possible.

An added challenge is that all of this is happening against the backdrop of a recent spate of shameful book bans that comes largely from the right. According to the American Library Association, of the hundreds of attempts to remove books from schools and libraries in 2021, a vast majority were made in response to content related to race and sex — red meat for red states, with Texas and Florida ranking high among those determined to quash artistic freedom and limit reader access. Republican politicians, for so long forces of intolerance, are now deep in the book-banning business.

We shouldn’t capitulate to any repressive forces, no matter where they emanate from on the political spectrum. Parents, schools and readers should demand access to all kinds of books, whether they personally approve of the content or not. For those on the illiberal left to conduct their own campaigns of censorship while bemoaning the book-burning impulses of the right is to violate the core tenets of liberalism. We’re better than this.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Pamela Paul became an Opinion columnist for The New York Times in 2022. She was previously the editor of The New York Times Book Review for nine years, where she oversaw book coverage and hosted the Book Review podcast. Her work has appeared in numerous publications, including The Atlantic, The Washington Post and Vogue.