Can Elon Musk break Twitter? I hope so.

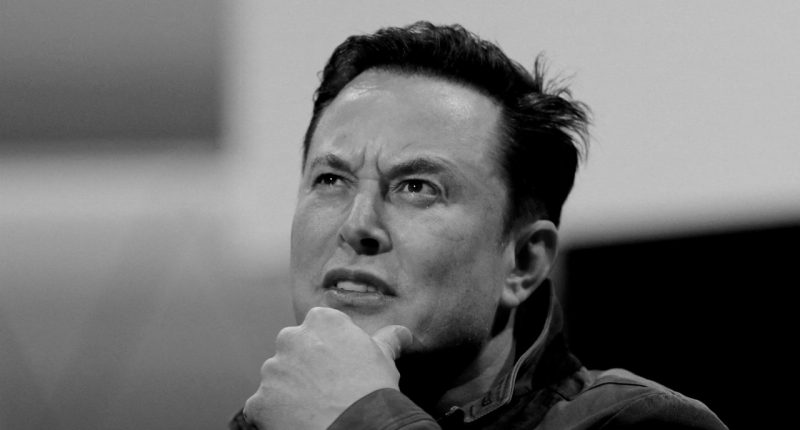

I’m not accusing Musk of being a sleeper agent. The man loves Twitter. He tweets as if he was raised by the blue bird and the fail whale. Three days before locking in his purchase of the platform, Musk blasted out an unflattering photograph of Bill Gates, and next to it, an illustration of a pregnant man. “in case u need to lose a boner fast,” Time’s 2021 Person of the Year told his more than 80 million followers. Musk believed Gates was shorting Tesla’s stock, and this was his response. It got over 165,000 retweets and 1.3 million likes. That’s a man who understands what Twitter truly is.

Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s co-founder and former chief executive, always wanted it to be something else. Something it wasn’t, and couldn’t be. “The purpose of Twitter is to serve the public conversation,” he said in 2018. Twitter began “measuring conversational health” and trying to tweak the platform to burnish it. Sincere as the effort was, it was like those liquor ads advising moderation. You don’t get people to drink less by selling them whiskey. Similarly, if your intention was to foster healthy conversation, you’d never limit thoughts to 280 characters or add like and retweet buttons or quote-tweet features. Twitter can’t be a home to hold healthy conversation because that’s not what it’s built to do.

So what is Twitter built to do? It’s built to gamify conversation. As C. Thi Nguyen, a philosopher at the University of Utah, has written, it does that “by offering immediate, vivid and quantified evaluations of one’s conversational success. Twitter offers us points for discourse; it scores our communication. And these gamelike features are responsible for much of Twitter’s psychological wallop. Twitter is addictive, in part, because it feels so good to watch those numbers go up and up.”

Nguyen’s core argument is that games are pleasurable in part because they simplify the complexity of life. They render the rules clear, the score visible. That’s fine when we want to play a game. But sometimes we end up in games, or gamelike systems, where we don’t want to trade our values for those of the designers, and don’t even realise we’re doing it. The danger, then, is what Nguyen calls “value capture.” That comes when:

1. Our natural values are rich, subtle and hard-to-express.

2. We are placed in a social or institutional setting which presents simplified, typically quantified, versions of our values back to ourselves.

3. The simplified versions take over in our motivation and deliberation.

Twitter takes the rich, numerous and subtle values that we bring to communication and quantifies our success through follower counts, likes and retweets. Slowly, what Twitter rewards becomes what we do. If we don’t, then no matter — no one sees what we’re saying anyway. We become what the game wants us to be or we lose. And that’s what’s happening to some of the most important people and industries and conversations on the planet right now.

Many of Twitter’s power users are political, media, entertainment and technology elites. They — we! — are particularly susceptible to a gamified discourse on the topics we obsess over. It’s hard to make political change. It’s hard to create great journalism. It’s hard to fill the ever-yawning need for validation. It’s hard to dent the arc of technological progress. Twitter offers the instant, constant simulation of doing exactly that. The feedback is immediate. The opportunities are infinite. Forget Max Weber’s “strong and slow boring of hard boards.” Twitter is a power drill, or at least it feels like one.

At about this point, the answer probably seems obvious: Log off! One can, and many do. But it comes at a cost. To log off is to miss much that matters, in industries where knowing what matters is essential. It’s become cliché to say Twitter is not real life, and that’s true enough. But it shapes real life by shaping the perceptions of those exposed to it. It shapes real life by shaping what the media covers (it’s not for nothing that The New York Times is now urging reporters to unplug from Twitter and reengage with the world outside their screens). It shapes real life by giving the politicians and business titans who master it control of the attentional agenda. Attention is currency, and Twitter is the most important market for attention that there is.

There is a reason that Donald Trump, with his preternatural gift for making people look at him, was Twitter’s most natural and successful user. And he shows how the platform can shape the lives of those who never use it. From 2017 to 2021, the White House was occupied by what was, in effect, a Twitter account with a cardiovascular system, and the whole world bore the consequences.

I am not a reflexive Musk critic. He has done remarkable things. He turned the electric car market from a backwater catering to hippies to the unquestioned future of the automobile industry, and he did so in the only sustainable way: He made electric cars awesome. He reinvigorated American interest in space and did so in the only sustainable way: by making rockets more awesome and affordable. He’s made huge investments in solar energy and battery innovation and at least tried to think creatively about mass transit, with investments in hyperloop and tunnel-drilling technology. He co-founded OpenAI, the most public-spirited of the big artificial intelligence shops.

Much of this has been built on the back of public subsidies, government contracts, loan guarantees and tax credits, but I don’t take that as a mark against him: He’s the best argument in the modern era that the government and the private sector can do together what neither can achieve apart. If anything, I fear that Twitter will distract Musk from more important work.

Nor am I surprised that a résumé like Musk’s coexists with a tendency toward manias, obsessions, grudges, union-busting and vindictiveness. Extreme personalities are rarely on the edge of the bell curve only because of benevolence. But Twitter unleashes his worst instincts and rewards him, with attention and fandom and money — so much money — for indulging them. That Musk has so capably bent Twitter to his own purposes doesn’t absolve him of his behavior there, any more than it absolved Trump. A platform that heaps rewards on those who behave cruelly, or even just recklessly, is a dangerous thing.

But far too often, that’s what Twitter does. Twitter rewards decent people for acting indecently. The mechanism by which this happens is no mystery. Engagement follows slashing ripostes and bold statements and vicious dunks. “I’m frustrated that Bill Gates would bet against Tesla, a company aligned with his values,” is a lame tweet. “Bill Gates = boner killer” is a viral hit. The easiest way to rack up points is to worsen the discourse.

Twitter has survived, and thrived, because it has never been just what I have described here. Much of what can be found there is funny and smart and sweet. So many on the platform want it to be a better place than it is and try to make it so. For a long time, they were joined in that pursuit by Twitter’s executive class, who wanted the same. They liked Twitter, but not too much. They believed in it, but they were also a little appalled by it. That fundamental tension — between what Twitter was and what so many believed it could be — held it in balance. No longer.

Musk’s stated agenda for Twitter is confusing mostly for its modesty. He’s proposed an edit button, an open-source algorithm, cracking down on bots and doing . . . something . . . to secure free speech. I tend to agree with technology writer Max Read, who predicts that Musk “will strive to keep Twitter the same level of bad, and in the same kinds of ways, as it always has been, because, to Musk, Twitter is not actually bad at all.”

Musk reveals what he wants Twitter to be by how he actually acts on it. You shall know him by his tweets. He wants it to be what it is, or even more anarchic than that. Where I perhaps disagree with Read is that I think it will be more of a cultural change for Twitter than anyone realizes to have the master of the service acting on it as Musk does; to have the platform’s master embracing and embodying its excesses in a way no previous leader has done.

What will Twitter feel like to liberals when Musk is mocking Sen. Elizabeth Warren on the platform he owns and controls as “Senator Karen”? Will they want to enrich him by contributing free labour to his company? Conservatives are now celebrating Musk’s purchase of the platform, but what if, faced with a deepening crisis of election disinformation, he goes into goblin mode against right-wing politicians who are making his hands-off moderation hopes untenable or who are threatening his climate change agenda?

What will it be like to work at Twitter when the boss is using his account to go to war with the Securities and Exchange Commission or fight a tax bill he dislikes? Unless Musk changes his own behavior radically, and implausibly, I suspect his ownership will heighten Twitter’s contradictions to an unbearable level. What would follow isn’t the collapse of the platform but the right-sizing of its influence.

Or maybe not. Betting against Musk has made fools of many in recent years. But I count myself, still, as a cautious believer in Musk’s power to do the impossible — in this case, to expose what Twitter is and to right-size its influence. In fact, I think he’s the only one with the power to do it. Musk is already Twitter’s ultimate player. Now he’s buying the arcade. Everything people love or hate about it will become his fault. Everything he does that people love or hate will be held against the platform. He will be Twitter. He will have won the game. And nothing loses its luster quite like a game that has been beaten.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Ezra Klein joined The New York Times Opinion in 2021. Previously, he was the founder, editor in chief and then editor-at-large of Vox; the host of the podcast, “The Ezra Klein Show”; and the author of “Why We’re Polarized.” Before that, he was a columnist and editor at The Washington Post, where he founded and led the Wonkblog vertical.