Half-way into January the Federal Government is still dithering on its May election promise to abolish temporary protection visas to refugees.

Anonymous sources reported in The Age have declared the government is granting permanent residency to 19,000 refugees on temporary protection visas and safe haven enterprise visas. But a decision and timeframe have not yet been officially announced, much to the ire and disappointment of advocates and refugees.

Equally, the question of what happens to 12,000 refugees seeking protection remains in the balance. While their applications for temporary protection visas have either been rejected, delayed or stuck in a protracted appeals process, they remain on bridging visas with limited or no access to work and study or health and welfare services.

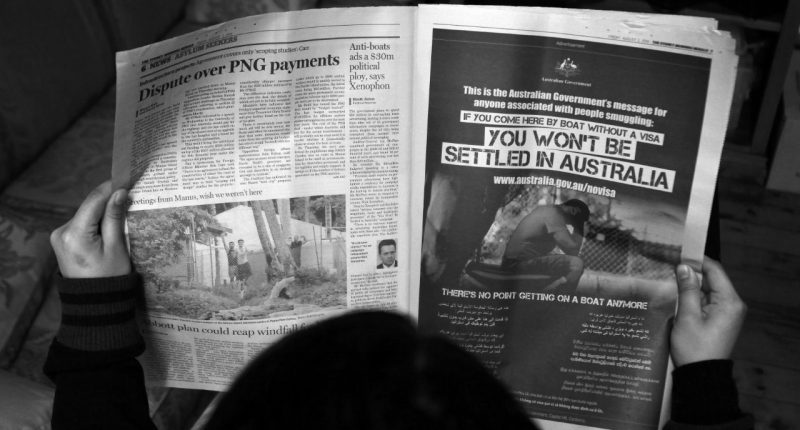

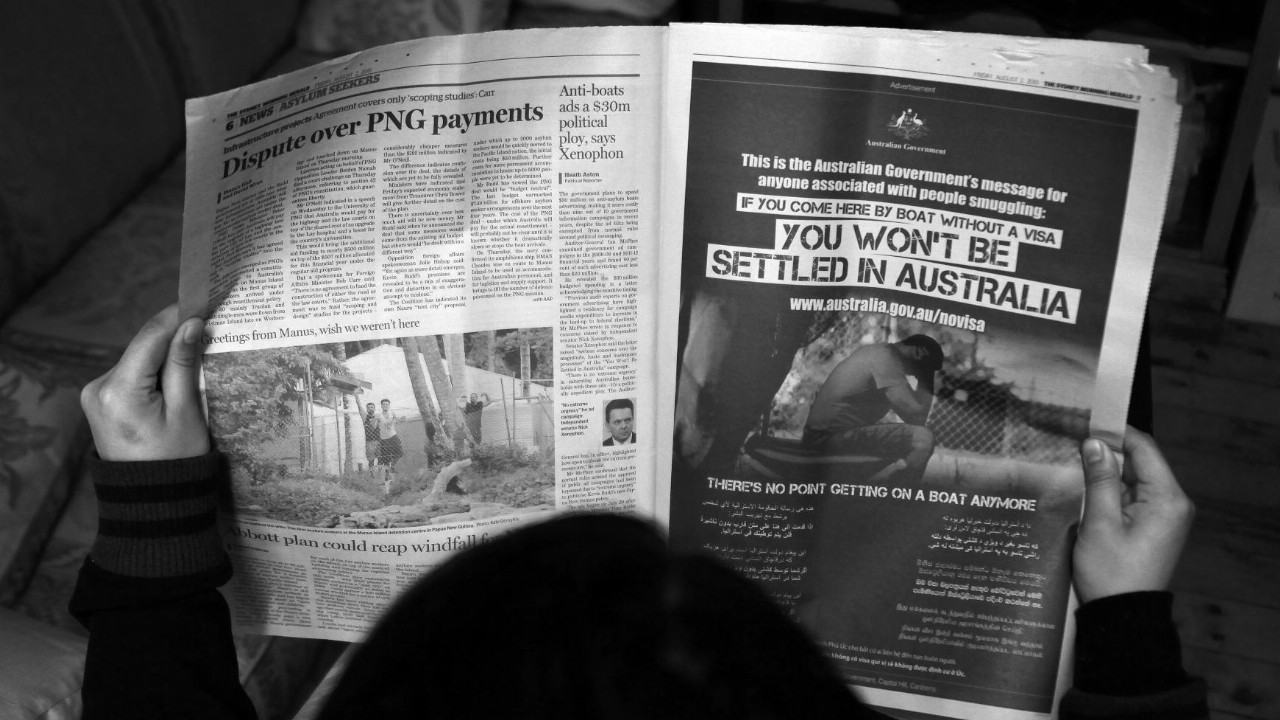

Part of the so-called “legacy caseload” of 31,000 people who have been in limbo for 10 years or more, they arrived in Australia by boat before 2014, originating mainly from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Sri Lanka, Sudan and Pakistan. Some are stateless.

All have been subjected to the so-called “fast-track” system — an oxymoron, as the refugee determination process has dragged on with scant or no resolution, and is regarded by advocates as a punitive and a deliberate deterrent.

No surprise refugee advocates have been inundated with calls over the festive period from refugees seeking clarity on the putative reforms despite the government’s repeated assurances it will abolish the system that facilitated temporary visas.

Late last year, Labor stated: “The existing fast track assessment process . . . does not provide a fair, thorough and robust assessment process for persons seeking asylum. Labor will abolish this fast-track assessment process.”

Replying to an appeal for action on January 8 by the Australian Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, one Twitter user responded: “No permanent status for 19,000 successful refugees after 10+ years. No one cares, how much your children suffering. Refugees need permanent residency certainty where they can live peacefully. No one left their home if you can live peacefully.”

The hallmark of a humane, democratic society, permanency would allow refugees full access to work and study security, mainstream social welfare support, family reunification and a sense of dignity. It also accords with Australia’s international obligations.

The dithering is political, says refugee activist Ian Rintoul from the Refugee Action Coalition.

“They are (the government) very concerned not to do anything that they think the Coalition may use to indicate they are soft on refugees or asylum seekers. They’re paralysed,” Rintoul said.

“It’s part of the punitive policies to try to deter people from seeking asylum in Australia.”

The Howard Coalition government introduced temporary protection visas in 1999. Then-immigration minister Philip Ruddock has been criticised for his hardline stance but doesn’t resile from it, saying the visas served a useful purpose in ensuring people didn’t expect to be permanently accommodated, provided Australia upheld its non-refoulement obligations under the Refugee Convention. That is, it is prohibited from returning a person to a country where they may be persecuted or tortured.

The major parties remain in lockstep on the boat turnback policy implemented in 2013, and mandatory and offshore detention. But the Refugee Council of Australia reports more support for Labor’s refugee policies than the Coalition’s, with 36 per cent of respondents preferring Labor’s policies over 32 per cent for the Coalition. Thirty-two per cent found no difference between the policies.

What does this say about the optics of Labor’s commitment to an election pledge for humane treatment?

“I wish politicians and bureaucrats knew the devastating impact that their lack of action has on people who have been in the community for a decade, denied the right to rebuild their lives and separated from their families,” says Jana Favero, director of advocacy at the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre.

“The lack of an announcement, the lack of clear communication and the lack of compassion from the government is harmful. Every day we’re being contacted by people subjected to the rigged fast-track system asking how they will get a pathway to permanency and when this will happen.”

If the government is dragging its feet on reforms because it regards them as complex, refugee advocates are not having a bar of it. Minister for Home Affairs, Clare O’Neil, blamed complexity for tardiness last year in a TV interview. But advocates point to the ease with which reforms can be implemented, and that it’s been Labor’s policy for years.

The Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law has also provided information on mechanisms available to the government for quick, effective reform within existing legislative provisions.

Yet, in comparison, refugees across the ditch have no such problems. New Zealand grants refugees full permanency rights when they arrive. In fact, Australia is the only country in the world to subject people it has formally recognised as refugees to temporary status, with no firm pathway to permanence.

New Zealand’s compassionate stance has precipitated strong community support, fostered refugee empowerment and self-sufficiency, and bolstered refugee services.

Pakistani ethnic Hazara, Liaquat Changezi, arrived in New Zealand with his family in 2018. Now a New Zealand citizen, Changezi — previously a documentary maker and news presenter for CNN — had wanted to return to media work when I met him in Indonesia in 2017 seeking resettlement. Instead, he’s devoted himself to helping the refugee community in his role as executive director of the Refugee Orientation Centre in Hamilton, in the North Island. Giving back to the community and the country he loves is his priority.

After the mosque shootings in 2019 in Christchurch, following the initial shock, his warmth for New Zealand grew. “People came forward and apologised,” Changezi said. He was surprised, saying Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, in taking serious action, was a great example: “This is a really beautiful country with such humble people.”

One of his daughters, Madiha, 23, is a law graduate in New Zealand and was invited to speak at the UN in October on refugee needs. Her ambition is to be an international human rights lawyer. In the meantime, she espouses refugee empowerment and self-sufficiency initiatives, with a focus on mental health, a major issue synchronous with cultural and language barriers.

“I want to make a difference,” she said.

Looking at the big picture, she is working towards global initiatives to give refugees the resources and tools to be more self-reliant, to pursue careers and to produce empowering programs using public funding well.

New Zealand’s refugee intake of 1500 a year is small compared with Australia’s 13,750. But Australia could perhaps take a leaf out of its neighbour’s resettlement strategy, which champions full refugee participation and integration “socially and economically as soon as possible so that they are living independently, undertaking the same responsibilities and exercising the same rights as other New Zealanders.”

Deborah Cassrels was The Australian’s first Bali-based correspondent and has written extensively on refugees, politics, terrorism, crime and social justice. She was nominated for a Walkley Award in 2016 for her work on terrorism in Indonesia. Her first book, “Gods and Demons”, a memoir about her journalism in Indonesia, was published in 2020.

Stay up to date on all the latest commentary, analysis and opinion pieces from Art of the Essay by following on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn.