In the months leading up to its premiere this Friday, Amazon Prime’s “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power” has prompted both excitement and concern among fans at the expansion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s world in the era of the “cinematic universe.”

Such intense interest may explain why Amazon Studios spent nearly $250 million for the rights to “The Lord of the Rings” — and roughly $1 billion more to produce the prequel series. But the investment is also part of a common strategy in Hollywood: Entertainment companies seem to have decided that owning the rights to beloved works, rather than producing original stories, is the key to maximising profits.

Established stories provide audience-tested settings in which multiple media products can be set, with all kinds of associated merchandise and “experiences” offering additional revenue. (See: the Marvel cinematic universe, Disney’s “Star Wars” and Universal’s Potterverse.) But not all stories are equally suited to being exploited by studios, and a Middle-earth that’s spread out — “like butter that has been scraped over too much bread,” to quote Bilbo Baggins — may not have the same appeal.

Entertainment executives can hardly be blamed for thinking Middle-earth could become just another lucrative “cinematic universe.” People love Middle-earth. They love the landscape, the languages and the deep histories that are built into Tolkien’s narrative. The desire not just to read about but go to Middle-earth is so strong that decades before Peter Jackson’s early 2000s film adaptations, enthusiasts were sewing costumes, learning Elvish languages and envisioning Middle-earth through fan art, poetry and fiction. (As a scholar of Tolkien’s works, I get regular requests to proofread tattoos that use Tolkien’s Elvish languages.) The cultural and linguistic cohesion that lends Middle-earth its magic is not so easily mimicked.

“The Rings of Power,” which will come out weekly after its two-episode premiere, is based primarily on only a few dozen pages in one of the historical appendices to “The Lord of the Rings,” meaning that almost the entire plot of the show has been created by Amazon Studios’ writers and showrunners. And there’s a huge gulf between Tolkien’s originality, moral sophistication and narrative subtlety and the culture of Hollywood in 2022 — the groupthink produced by the contemporary ecosystem of writers’ rooms, Twitter threads and focus groups. The writing that this dynamic is particularly good at producing — witty banter, arch references to contemporary issues, graphic and often sexualised violence, self-righteousness — is poorly suited to Middle-earth, a world with a multilayered history that eschews both tidy morality plays and blockbuster gore.

Is it fair to the legacies of writers like Tolkien to build franchises from their works without their knowledge or permission? Tolkien, who died in 1973, was fiercely protective of the world he created in his novels. He harshly rejected the spec screenplays of “The Lord of the Rings” he read and once asserted that the work was not appropriate for film. (He sold the film rights in 1969 only in order to help pay a tax bill; the television rights were sold to Amazon by his heirs.)

His biographer reports that, when attending a production of “The Hobbit” adapted as a children’s play, Tolkien frowned every time the dialogue departed from what he had written. So it is hard to believe that he would have approved of a team of writers building almost entirely new stories with little direct basis in his works.

Tolkien was probably right to be so wary. The demands of scaling up beloved works into broader franchises often proves incompatible with the unique visions that drew the original audiences. And it’s worth noting that author involvement — like that of J.K. Rowling in the “Fantastic Beasts” films, for example — is no guarantee that derivative works in a different medium will have the special qualities that made the originals successful.

Many of the most popular cinematic universes have been born of visually centred mediums: “Star Wars” in film, “Star Trek” in television, and Marvel in comic books. Adapting literary works into franchises has a less auspicious history, especially when screenwriters wander far from their source material. The “Game of Thrones” series, for example, was widely panned after it left George R.R. Martin’s books behind.

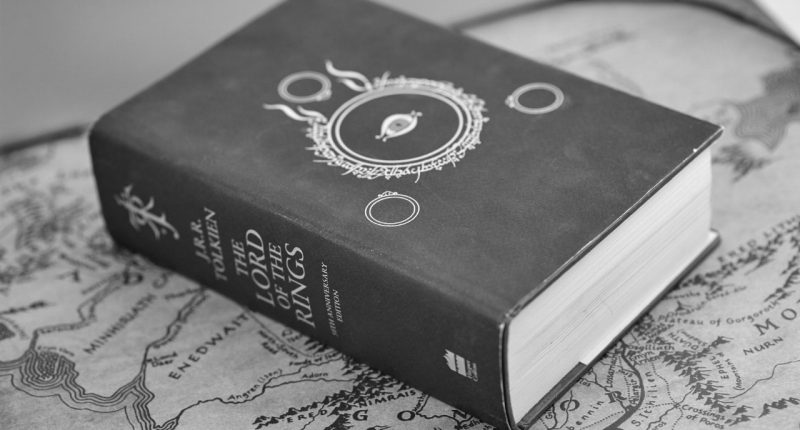

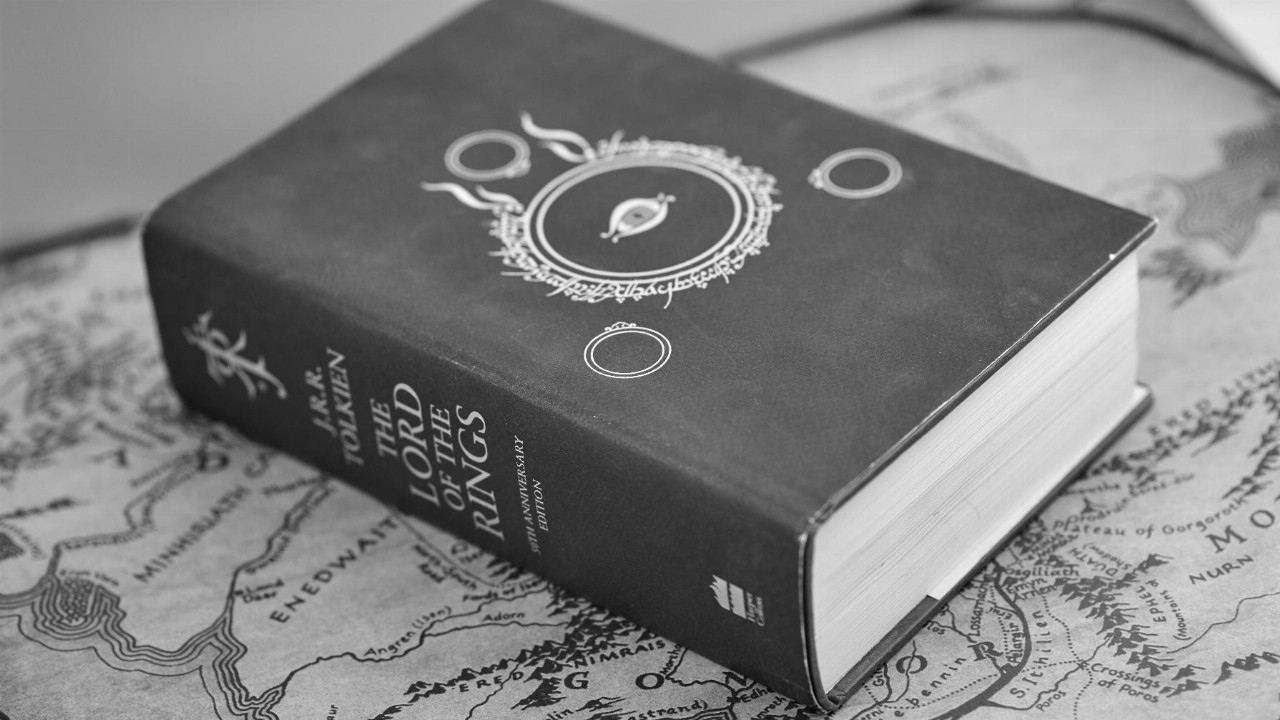

Tolkien’s works may be still harder to adapt. A professor of medieval literature who as a young man helped write the entries for words including “wasp,” “wain,” and “walrus” in the Oxford English Dictionary, Tolkien wrote a deeply textured prose that is vastly different from that of his fantasy imitators. It evokes the flavour of Anglo-Saxon epic poetry and Old Norse sagas, giving readers the sense that they are reading something very old that has been translated by Professor Tolkien, not composed by him.

Tolkien’s narrative craftsmanship is both dramatic and subtle. He writes from the point of view of his least knowledgeable characters (usually hobbits, but occasionally Gimli or Gollum and once even a confused fox), so they and the reader learn about the world beyond the Shire together, piecing together Middle-earth through hints and fragments. No wonder people say that reading “The Lord of the Rings” feels more like an experience than a book — cognitively, it is. And that is precisely the sort of effect that can translate poorly onto film, particularly when a series has to work from a brief summary.

Not just character but moral clarity can be easily lost when a team of writers, inherently beholden to the concerns, politics and tropes of the day, takes over from a single author and attempts to build a narrative that will best support a studio’s desire for a never-ending revenue stream.

What makes Tolkien’s work unique is the moral heart of his story and the consistency with which he maintains it. Rather than revelling in the acquisition and exercise of power, “The Lord of the Rings” celebrates its renunciation, insisting that the domination of others is always morally wrong. Tolkien is utterly consistent with this morality, even at the expense of his most cherished characters: Frodo has no other choice than to use the power of the Ring to dominate Gollum, but he still pays for that immoral act when he is unable to complete his quest or to enjoy his life afterward. Can a company as intent upon domination as Amazon really understand this perspective — and adapt that morality to the screen?

If viewers find themselves disappointed by “The Rings of Power,” it will probably not be because the computer-generated imagery is second-rate or there are not enough fight sequences. It will be because the new adaptation lacks the literary and moral depth that make Middle-earth not just another cinematic universe but a world worth saving.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Michael D.C. Drout is the chair of the English department of Wheaton College in Massachusetts and a co-editor of Tolkien Studies.