Earlier this year, Harvard unveiled a report of the university’s history of profiting from slavery. “I believe we bear a moral responsibility to do what we can to address the persistent corrosive effects of those historical practices on individuals, on Harvard and on our society,” Lawrence Bacow, the university president, wrote in an open letter to the community. The study was heralded as a long overdue reckoning by an elite institution with its dark past.

But tackling its role in the American slave trade only addresses one aspect of the school’s past. Harvard still boasts a fellowship and a professorship named for Alfried Krupp, a Nazi war criminal whose industrial empire used around 100,000 forced labourers.

Harvard is not alone: From NASA to Stanford to the United States Army, American institutions continue to acknowledge — and sometimes even celebrate — high-profile former Nazis.

The individuals honoured aren’t obscure Holocaust guards who managed to skulk past immigration officers — some of them are historical figures whose relationship with America has been extensively chronicled, including in well-researched tomes by Eric Lichtblau and Annie Jacobsen.

The institutions that whitewash the Nazi past of men whose names grace Harvard and Stanford programs, part of NASA’s Kennedy Space Centre and multiple locations in Huntsville, Alabama, typically do so via deception by omission — erasing history by leaving out or sidelining inconvenient facts.

How did the United States go from fighting the evil of Nazism to lauding ex-Nazis? It began with the end of the wartime honeymoon between Moscow and the West. With Germany divided and defeated, Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union quickly became America’s biggest enemy. Washington needed technology to compete with the Kremlin and a solvent West Germany to serve as a bulwark against Communism spreading through Europe. The ex-Nazis offered tantalising expertise. So while a handful of prominent Third Reich figures were hanged in Nuremberg, many others saw their noxious pasts wiped clean as they became partners and allies in the Cold War.

By the 1960s, with the Space Race well underway, the former S.S. officer Wernher von Braun found himself meeting with U.S. presidents and being presented by the media as a math wizard working to get America to the moon. In other words: We didn’t just hire him, we made him a hero.

Just shy of 30 years after the war, there was barely a ripple of surprise when it was announced that Harvard would receive $2 million (approximately $12 million today, adjusted for inflation) from the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation. It was 1974, and the funds were used to establish the Krupp Foundation Professor of European Studies as well as the Krupp Foundation Dissertation Research Fellowship.

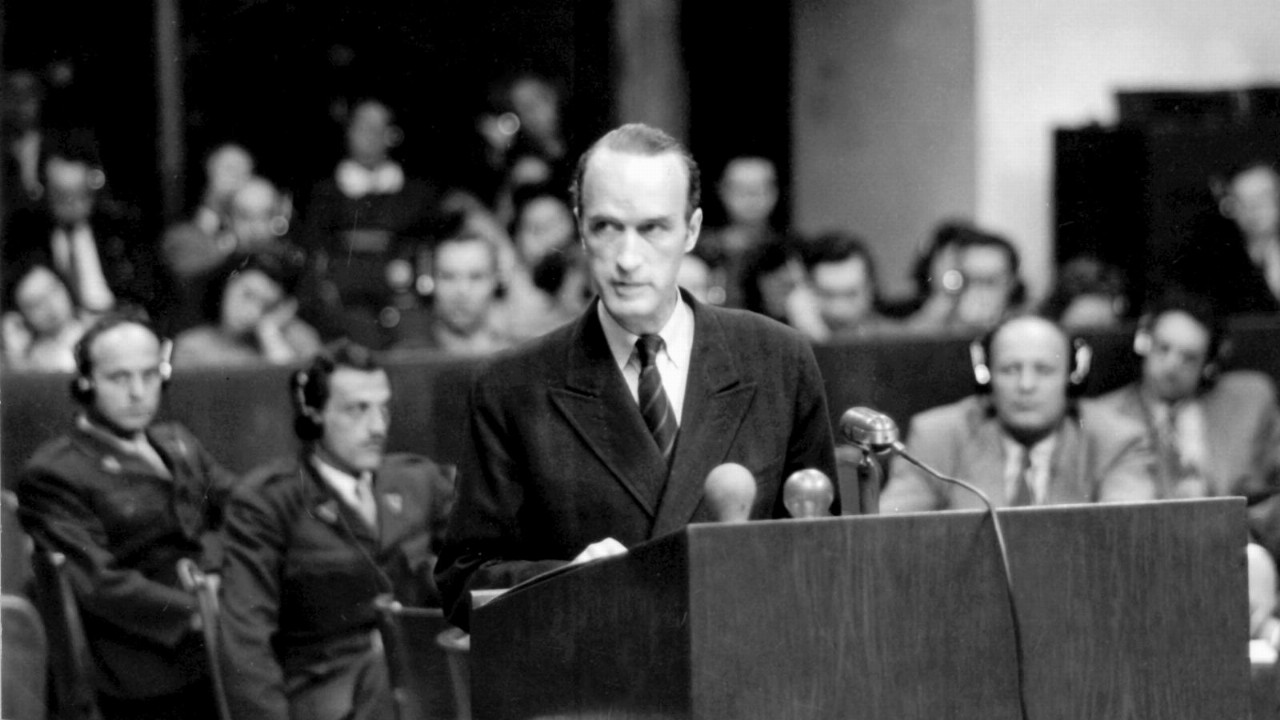

Alfried Krupp was an industrial baron and was convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Nuremberg. His company had a slave-built factory in Auschwitz and put to work approximately 100,000 forced labourers, including prisoners of war, concentration camp inmates and children. When Harvard accepted Krupp’s money, The Harvard Crimson published a letter stating that “few names are more honoured in the annals of mass murder and genocide than that of Krupp.” (In 1951, Krupp’s sentence was commuted and he was released from prison.)

The web pages for Harvard’s Krupp fellowship and the Krupp professorship say nothing about their namesake being a convicted war criminal.

The Krupp Foundation also sponsors Stanford’s Krupp Internship Program for Stanford Students in Germany, advertised as a “unique and prestigious program.” The fact that Krupp was a war criminal is only mentioned once on the program’s webpage.

But the rehabilitation of Krupp pales in comparison to America’s overt whitewashing of von Braun and Kurt Debus, two of the Third Reich scientists responsible for giving Hitler the deadly V-2 ballistic missile. The V-2 was built by concentration camp prisoners toiling under abhorrent conditions in Germany’s infamous underground complex near Dora-Mittelbau. At least 10,000 enslaved people were killed in the process of making the rockets; American troops liberating the concentration camp were sickened when they discovered a ghastly plateau strewn with emaciated corpses.

But von Braun’s and Debus’s membership in the Nazi Party didn’t preclude them from being offered jobs via Washington’s infamous Operation Paperclip program that recruited former Nazi scientists to work in America.

Von Braun eventually moved to Huntsville, which became a centre for America’s budding space industry. Today the city and surrounding area houses a number of shrines to the former Nazi: His name graces a research hall at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, a performing arts centre and a planetarium.

“Dr. Wernher von Braun and his team of rocket scientists transformed Huntsville, Alabama, known in the 1950s as the ‘Watercress Capital of the World’, into a technology centre that today is home to the second largest research park in the United States,” proclaims the “About Us” section of the U.S. Space and Rocket Centre — a Smithsonian-affiliated museum and the home of the renowned Space Camp program. (A spokeswoman for the centre said, “we are in a current redevelopment of the Rocket Centre’s website affiliated Space Camp pages,” and that the centre intends to provide additional context.)

In the meantime, von Braun is lauded at practically every turn: on the Space Camp website, on the University of Alabama in Huntsville’s school history page, in the description of the Dr. Wernher von Braun Scholarship, even in a 2019 speech by Robert Altenkirch, who was then the university president — none of which mention Nazis or slave labour. (The school does have a web page about rocketry and slave labour that mentions von Braun.)

As for the von Braun Centre performing arts venue, a spokesperson for the city of Huntsville said that there is “an ongoing effort to provide greater historical context and information” on the centre’s website. But how long does it take to correct the record?

The impression one gets from these sanitised histories is that this was a man who had materialised out of nowhere, with no discernible past, like an astrophysical Mary Poppins who had come to teach the people of Huntsville how to make rockets.

It seems it is less common to note a Nazi past than to look past it. Such is the case with the NASA Kennedy Space Centre’s visitor complex in Florida, which is home to the Dr. Kurt H. Debus Conference Facility. In the official NASA biography of Debus there is but a short, vague paragraph about his life in Germany. On June 24, the Kennedy Space Centre’s director, Janet Petro, accepted the National Space Club Florida Committee’s Dr. Kurt H. Debus Award; NASA’s webpage celebrating the event referenced Debus’s astronomical achievements, noting nothing of his S.S. membership and intimate involvement with building the V-2.

Perhaps the most astonishing example of Nazi laundering comes from the Redstone Arsenal, a U.S. Army post next to Huntsville, which has a building complex named after von Braun. The arsenal’s history section features dozens of photos of von Braun, while his bio says he was “employed by the German Ordnance Department” and was the technical director of the centre where the V-2 was developed. No mention is made of how the V-2 was used by the Third Reich to unleash hell on civilians.

Though our military is slowly dealing with its numerous tributes to the Confederacy, it has yet to adequately address its lionisation of a man who built weapons for Hitler. It is astounding that institutions like the Army, NASA and leading universities persist in insulting the sacrifice of thousands of American soldiers by openly celebrating Nazi weapon makers.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Lev Golinkin is the author of the memoir “A Backpack, a Bear and Eight Crates of Vodka”.